| Separation,

Awakening and Revolution |

I've just dipped into the online version of a

a book by Charles Eisenstein, called "The Ascent of Humanity".

All 600 pages of it is

available online, on a voluntary donation basis. I'm stilled by

awe. For those of us who are trying with all our might to connect

the avalanche of dots in the complex unfoldment of modern civilization,

this book is a clarion call. If you are

interested in the questions, "Where

are we?", "How did we get here?",

"What comes next?", and

especially "WTF is going on?",

then

if you read no other book this year (or this decade, for that matter)

read this one. I've just dipped into the online version of a

a book by Charles Eisenstein, called "The Ascent of Humanity".

All 600 pages of it is

available online, on a voluntary donation basis. I'm stilled by

awe. For those of us who are trying with all our might to connect

the avalanche of dots in the complex unfoldment of modern civilization,

this book is a clarion call. If you are

interested in the questions, "Where

are we?", "How did we get here?",

"What comes next?", and

especially "WTF is going on?",

then

if you read no other book this year (or this decade, for that matter)

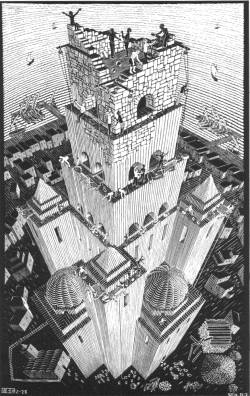

read this one. Eisenstein's argument is briefly sketched in the following excerpts: The

myth of technological utopia is uncannily congruent to the

religious doctrine of Heaven, with technology as our savior. Thanks to

the god Technology, we will leave behind all vestiges of mortality and

enter a realm without toil or travail and beyond death and pain.

Omnipotent, technology will repair the mess we have made of this world;

it will cure all our social, medical, and environmental ills, just as

we escape the consequences of our sins of this life when we ascend to

Heaven.

(...) Underlying the Technological Program is a kind of arrogance, that that we can control, manage, and improve on nature. Many of the dreams of Gee Whiz technology are based on this. Control the weather! Conquer death! Download your consciousness onto a computer! Onward to space! All of these goals involve controlling or transcending nature, being independent of the earth, independent of the body. Nanotechnology will allow us to design new molecules and build them atom by atom. Perhaps someday we will even engineer the laws of physics itself. From an initial status of subordination to nature, the Technological Program aims to give us mastery over it, an ambition with deep cultural foundations. Descartes' aspiration that science would make us the "lords and possessors of nature" merely restated an age-old ambition: "And God said to them, Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth" (Genesis 1:28). (...) When we separate ourselves from nature as we have done with technology, when we replace interdependency with "security" and trust with control, we separate ourselves as well from part of ourselves. Nature, internal and external, is not a gratuitous though practically necessary other, but an inseparable part of ourselves. To attempt its separation creates a wound no less severe than to rip off an arm or a leg. Indeed, more severe. Under the delusion of the discrete and separate self, we see our relationships as extrinsic to who we are on the deepest level; we see relationships as associations of discrete individuals. But in fact, our relationships—with other people and all life—define who we are, and by impoverishing these relationships we diminish ourselves. We are our relationships. (...) For people immersed in the study of any of the crises that afflict our planet, it becomes abundantly obvious that we are doomed. Politics, finance, energy, education, health care, and most importantly the ecosystem are headed toward near-certain collapse. During the ten years I've spent writing this book, I have become familiar with each of these crises of civilization, enough to get some sense of their enormity and inevitability. Every year I would wonder whether this might be the last "normal" year of our era. I felt the dread of what a collapse might bring, and visited the despair of knowing that our best efforts to avert it are dwarfed by the forces driving us toward catastrophe. (...) It is not my purpose to persuade you that we indeed face an environmental, financial, political, energy, soil, medical, or water crisis. Others have done so far more compellingly than I could. Nor is it my aim to inspire you with hope that they may be averted. They cannot be, because the things that must happen to avert them will only happen as their consequence. All present proposals for changing course in time to avert a crash are wildly impractical. My optimism is based on knowing that the definition of "practical" and "possible" will soon change as we collectively hit bottom. Another way to put it is that my optimism depends on a miracle. No, not a supernatural agency come to save us. What is a miracle? A miracle comes from a new sense of what is possible, born from a surrender of the attempt to manage and control life. The changes that need to happen to save the planet are the same. No mainstream politician is proposing them; few are even aware of just how deep the changes must go. For many people, the convergence of crises has already happened, propelling them, like the hippies or Taoist Immortals, into a release of controlled, bounded, separate conceptions of self, away from the technologies of separation, and toward new systems of money, education, technology, medicine, and language. In various ways, they withdraw from the apparatus of the Machine. When crises converge, life as usual no longer makes sense, opening the way for a rebirth, a spiritual transformation. Mystics throughout the ages have recognized that heaven is not some distant, separate realm located at the end of life and time, but rather is available always, interpenetrating ordinary existence. (...) What is special about our age is that the fulfillment of processes of separation on the collective level are causing this personal convergence of crises, and the subsequent awakening to a new sense of self, to happen to many people all at once. This article is not a book review. If this topic interests you as deeply as it does me, then the book will recommend itself. Go read it (and contribute to the author when you do). Rather than a review, what follows is my own thinking as recently shaped and refined by Eisenstein's work. As a bit of background, my early spiritual education in the late 60s and early 70s was filled with Alan Watts, Zen Buddhism, Taoism and some of the teachings of Osho. Then, like so many of my contemporaries, I forgot about it. Instead I decided to cut my hair, settle down, get a real job and make some real money. Not all of the lessons from those days were laid aside forever, though. It's easy to sell out, but much harder to stay sold. Now at 57 years old I'm back: to Zen, Taoism and Osho, but with the additional flavourings of William Catton (Ecology), Arne Naess and Joanna Macy (Deep Ecology), John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen (anarcho-primitivism) and Eckhart Tolle. With that as context, here are some thoughts on the questions I asked above. I'm in full agreement with Eisenstein that the basic problem of modern civilization is that we have separated ourselves in a deep fundamental way from nature and the rest of the universe. That separation (the dualism of man vs. nature, us vs. it, spirit vs. matter) gave rise to the cultural narrative we tell ourselves – the co-created memetic fabric in which we all function. This dualism and the tools that sprang from it gave us insulin, but they also gave us the Love Canal. The question to me is whether the benefits of our separation have been worth the price. Perhaps at a deeper level the question is whether the apparent benefits are even real or if we simply define them as benefits so as to support our cultural narrative. It comes down to what we decide "better" means. The one aspect of this situation that makes me certain to my core that the benefits have not been worth the cost is the impact that our cultural narrative of "growth and dominion" has had on the rest of the living planet. It's not "hubris" in the colloquial sense that has caused us to do (and accept) this damage. This sort of hubris is a consequence of our separation, as is the "growth and dominion" narrative of which it is an expression. First we set ourselves apart from nature, then we set ourselves above it, arrogating to our species the right to manipulate all of nature to our own ends. Even overpopulation is better understood as merely a consequence of our separation rather than simply as one source of our current troubles. Of course, the exact same understanding applies to the flip side of that coin, overconsumption. The root cause of both overpopulation and overconsumption is our belief that we are separate from the the natural world. Until that basic separation is healed, all attempts to "fix" both overconsumption and overpopulation are doomed to failure. The overarching fear that so many people feel when faced with the possibility that our path of "growth and dominion" may falter is the result of an egoic identity crisis. We take our identity largely from the world outside rather than from within ourselves, which is yet another legacy of separation. As a result when the outside world changes our sense of self is threatened, and we feel this as the threat of dissolution or annihilation. This is why such Herculean effort is being expended to preserve business as usual – to keep driving, farming, consuming, communicating just as before, no matter what changes occur in the outer world. For many of us, any deviation from that path carries a threat of psychic annihilation that is too painful to accept, or even admit. Regarding the anarcho-primitivism I mentioned above, I think it's a very perceptive philosophy when it comes to identifying how we got into this mess. However, after reading more of Derrick Jensen's two volume opus "Endgame" in the last couple of weeks, I've decided that the "ecodefense" aspect of that stream that promotes the active destruction of civilization holds no answers for me, though for perhaps slightly unusual reasons. The first reason is that the playing field of our civilization is owned by the Guardian Institutions. They define the game, they set the rules and enforce them. If you play on that field, you axiomatically accept the definition of the game that is in play. Then, you either follow the rules or you are penalized. And the Guardian Institutions are (or at least pay for) the referees. In a less abstract way, it works like this: The world's power brokers have long since defined material growth as the Primary Good of civilization. To enable that growth they promote and defend the view that humanity is the only species of importance, and that everything else on the planet, living or not, is part of our resource base. They do everything in their power to co-opt people into their world view, in the name of reducing resistance to it. In effect, "we" become "them" Whenever anyone attempts to challenge that view directly, they are treated like foreign cells within a living body. Our civilization has an immune system composed of courts, police, legislatures and editorial boards that leap to neutralize such interlopers. The price exacted from a person or group for attacking the body of civilization is precisely the same as the price paid by an intruding disease cell in a living body – annihilation. The immune system of civilization is both powerful and pervasive because it consists not just of "them", we are a part of it too. As a result direct attacks on a functioning civilization are pretty much doomed from the outset (attacks on a failing civilization, like diseases in a body with a failing immune system, are of course a different story). While the power brokers of civilization may from time to time grant their opponents some small victory (like Clayquot Sound, for instance), the idea of permitting popular action to assault the basis of civilization is just not in the cards. A more subtle reason why direct anti-civilization action is a poor idea is that it is by definition conducted within civilization's rules. The simple fact that you fight against those rules means that even if you don't think you are bound by them you are bound to them. In Buddhist language this is an attachment, and as such leads to suffering. An inability to detach from something means you are in some way dependent on it for your identity (sound familiar?). As a result, the civilization/anarchist dialectic cannot result in a transformation of our situation, because each is bound to the other, and in some sense is dependent on the other. What will resolve this situation is not some variation of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, but transformation – we need a true revolution. What form might this revolution take, if it can't use the current situation to define itself? It must emerge in some sense orthogonal to the existing narrative. The conclusion I've come to is that it requires a transformation in consciousness. In order to heal our separation from nature, we must heal the separation within ourselves. Fortunately that is possible, and a lot of groups (like The Inner Journey that I'm part of) specialize in doing just that. Once that process is underway, you become less and less accessible to the Guardian Institutions, because the things you are trying to circumvent through your awakening are precisely the implanted filters, patterns and programs that they rely on to maintain their game. If you can place yourself beyond their psychic reach, you become a free agent. Personal awakening is the one true revolutionary act. Its power and consequences far outweigh any petition, sit-in, or even bombing a dam or impeding whalers. While you may sometimes feel that personal awakening doesn't amount to much in comparison to the pervasive global might of civilization, remember that the derogatory voice in your head telling you this is not your own. It is really just more of the Guardian Institutions' programming: "We are the True Borg, there can be nothing outside of us, resistance is futile." Don't believe that voice for a second – there is a good reason why the guardians try so hard to marginalize this course of action. It is the single most powerful thing any of us can do. Awakening won't directly give you the answers on to how to lead your life. It will allow you to recognize those answers when they appear in front of you. And that, my friend, is true personal power. November 2, 2008 Comments

|

|

©

Copyright 2008, Paul Chefurka

This article may be reproduced in whole or in part for the purpose of research, education or other fair use, provided the nature and character of the work is maintained and credit is given to the author by the inclusion in the reproduction of his name and/or an electronic link to the article on this web site. The right of commercial reproduction is reserved. |